maroun.c

Moderator

View Badges

Staff member

Super Moderator

Excellence Award

Reef Of The Month

Photo of the Month

Article Contributor

My Tank Thread

Tank photography has been and continues to be a challenging topic for many reefers. When I started my tank, I was using an SLR (a non-digital for the newer generation); yes, we used to shoot using film and wait for days to finish the roll and get it developed. I remember taking notes on how each shot was taken (no Exif info was available then) and then keeping the notes to compare with the pictures when the film was processed. I was able to raise my ratio of good shots from 2/36 to 25-30/36 in less than a year through this process of trial and error. I doubt anyone is still behind a film camera these days; however, looking at it years afterward, the annoying wait time for the film to be shot, processed, and printed pictures received did provide a great feeling of self-satisfaction with every successful shot. It also led to checking out parameters and composition much more than we do now where we tend to shoot…correct…and shoot again till we get a good shot.

Fast forward 10 years, and we find ourselves utilizing digital point and shoot cameras (which have come a long way I must admit), entry level DSLRs, crop sensor DSLRs, and again back to full frame DSLRs, and (to make it weird) even small mobile phone cameras that surprisingly can now compete with high-end DSLRs (or so our minds have evolved to think)!

Understanding photography principles relates to understanding the physics behind it. This learning curve can really annoy many people (myself included). I did my best to read up on those principles and to understand them to some extent, but I found out that testing those and seeing the results in actual shots is the best way to fully understand. This 6-part article series won’t delve into complex photography physics and will focus more on straightforward facts and representative pictures to show the effects. In this article, I will address the following list of topics which are most frequently mentioned on aquarium photography forums:

1. Challenges of aquarium photography

2. Camera positioning and stabilization

3. Aperture

4. Shutter speed

5. ISO

6. Depth of field

7. Focusing

8. noise

9. Lighting

10. White balance

In future articles in this series, I will devote time to covering:

11. Preparing for a photoshoot

12. Fish/Coral Camera settings

13. Shooting with Cameras Vs Mobile phones

14. Taking better pictures with mobile phone cameras

15. Top down shots

16. Post-processing

1. Challenges of Aquarium photography

The following factors make photographing fish and corals in tanks at least different or more challenging than common photography:

To start with, we are shooting through a thickness of glass. Remember that photography lenses are mostly expensive due to the high cost of high end glass used (a lens or a zoom is a series of internal lenses used and, of course, technology like vibration reduction, autofocusing mechanism…). Another type of glass that we shoot through is the expensive lens filters that are added in front of lenses for some effects. These are simply a piece of glass with a mount. Now consider shooting through an increased thickness of green tinted glass with algae film buildup and scratches. Furthermore, we are often shooting at even more thickness than we think simply because we may angle the camera a bit instead of being totally perpendicular to the aquarium glass which can only increase distortions. To make it even worse, the aquarium glass adds the challenge of reflection that can limit use of flash.

An additional challenge is the particles floating in the water, distorting the clarity of the photo. The medium we’re shooting in (water) also plays an important role. Keep in mind, this is water where we have flow…stirring all sorts of debris from feeding and fish excrements, as well as particles released from some corals. Tank water is not always clear and can have a yellowish/green tint (Don’t believe me? Simply compare two cups tank water/fresh water). We’ll go through some techniques to make sure the water is as clear as possible before a photoshoot which can help, yet we have to keep in mind that water is not as clear as we perceive it to be, and this will lead to some challenges. To make it worse certain fish are constantly picking algae from rocks, picking the sand for critters or even diving in the sand which makes for frequent release of particles we have to deal with when taking pictures.

Additional challenges are the subjects we shoot which are constantly on the move. This makes photographing a fish even more difficult than getting a 5-year-old to stay still for a picture. Even corals are mostly swaying in the current, and stopping the flow can lead to unnatural shapes or at least take away from their beauty.

Tank lighting is one of the most difficult challenges to deal with, and LEDs have made it so much more difficult to take good-looking pictures with natural looking colors. Unfortunately, cameras can’t “see” or correct for white balance the same way our eyes and mind can, which results in blue-looking pictures most of the time. Oddly, our minds have somehow accustomed to that and I see blue pictures shared on forums and on social media. It’s even worse for out of focus pictures (which I will go through when discussing aperture and DOF).

2. Camera positioning and stabilization

Considering that we are shooting through glass as described above, it makes sense to minimize distortion by shooting through the least amount of glass. The easiest way to do this is to be totally perpendicular to the glass. Refraction and reflection are also the least when we take photos at a perpendicular angle rather than at an oblique angle.

Oblique camera position and resulting distortions in the picture

Glass can also make it more challenging with reflections from ambient lighting as well as from flash lighting used.

Ambient light reflections showing 2 different effects based on tank lighting

To best cope with ambient light and reflections, dimming room lights, closing shutters and positioning front lens (it’s better to have a lens hood on to avoid scratches and to better tell if the camera is perpendicular to front glass)

If shooting handheld rather than with a tripod, using a lens hood can also offer a level of support to avoid handshake. If on a tripod, I also try to position the camera so that the front lens is perpendicular and very close to the glass in order to avoid reflections and distortions. This level of close proximity to the aquarium also serves to keep tiny scratches that might be in the tank glass invisible in pictures. Cameras also have a minimum focus distance which causes obstructions in close proximity to the lens to become blurred, and consequently, they won’t appear in the picture. This is useful for avoiding scratches and tiny algae spots on glass from showing in your photo.

Camera hand held Perpendicular to glass

(Top down shots are gaining in popularity lately, especially as most corals posted for sale online are shot top down, we’ll discuss those in a later article in this series).

A steady tripod is a must in tank photography as we are mostly shooting at reduced shutter speed due to lower light levels, this increases the chance for camera shake. I find a good tripod and a decent tripod head (tripods and tripod heads come separate for professional tripods which allow you to match tripod heads to the camera and lenses you are using) are very beneficial. Go for sturdier models if shooting with heavy camera/lens combination.

Joystick tripod heads also offer a higher degree of flexibility especially when tracking moving fish, I find them very useful especially when using a monopod VS a tripod. Monopods can be a be a bit easier to carry around and more flexible to use for aquarium photography but not as steady as tripods.

Monopod and joystick head

Tripod and ball head

3. Aperture

Aperture, shutter speed, and ISO are the three photography pillars, and understanding those is crucial to understanding what went wrong (or right) in a picture and how to correct it or what to do to get a desired effect.

Let’s discuss aperture first. In simple words, aperture is the measure of the size of the opening of the lens when taking a picture. The more open it is, the more light it allows through the lens, which allows the camera to better adjust for dim lighting. However, increased aperture comes at a price which is depth of field (DOF), or how much distance away from our focus point is in focus (not blurred). To make it more complex, the numbers are inverted so the smallest aperture has the biggest number. Different lenses have different apertures—2.8 and below is considered pro.

So basically:

A shot at 2.8 aperture (very wide aperture) will allow more light in, but DOF will be limited.

A shot at 32 (very narrow aperture) will allow very limited light to go through yet it provides more depth of field so that objects before or after the point of focus will appear in focus.

Common aperture numbers go as follows: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22… Reducing aperture size at multiples of one over the square root of two allows half the light into the camera. For example, f/8 will let in 4 times more light than f/16. The effect on depth of field and lighting is clearly seen on the photos of the ruler (see below) where the focus point is on 5.

Pictures at 2.8-4.0 and 8.0 aperture. Focused at 5. Notice how DOF increases with Aperture (more of the image in focus) and how the amount of light in the picture decreases with smaller apertures.

Pictures at 2.8-4.0 and 8.0 aperture. Notice how DOF increases with Aperture (more polyps appear in focus) and how shutter speed was compensated (slower shutter speed for smaller aperture) to keep exposure constant. Last picture shows the effect of increasing aperture without shutter speed compensation which results in a darker image.

4. Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is the length of time set for the shutter to remain open while taking a picture. The more it stays open, the more light goes into the camera, and naturally, the more chance for our subject or hands to move and cause blur to happen. Sometimes blur is a desired effect, and we choose to go with longer exposures to get the blur that reflects motion like moving water in a river. However, in aquarium photography we mostly prefer crisp shots, so faster shutter speeds are used to freeze any motion.

Shutter speed is measured in fractions of a second: 1/1000, 1/500, 1/250, 1/12, 1/60, 1/30, 1/15, 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 1

Speeds as fast as 1/8000 of a second and as long as 30 Seconds (or even B exposure which leaves the shutter open till manually closed) are available on most newer cameras. Longer exposures are rarely needed in aquarium photography, and ultra-fast exposures are rarely possible with limited tank lighting.

Flash is frequently used to freeze the motion of a fish while a little longer exposure can gather up enough light to illuminate the background or a fast shutter speed is used to black out the background

Motion blur visible at shutter speed of 1/6 and decreases at shutter speeds of 1/25 and 1/60. Shutter speeds of 1/125 possible by increasing ISO to 400 and to avoid a very wide aperture that would minimize DOF.

Effect of shutter speed on motion blur, with fish looking blurry on shutter speed of 1/20 with particles in the water looking blurred as well.

Shutter speed of 1/125 to freeze motion, flash used to keep a good exposure.

5. ISO

ISO is the camera’s sensitivity to light. In film days, different films had different sensitivity and selection was based on what type of subjects were being photographed.

Digital photography has made it easy to switch ISO (a simple button click now), which modifies the sensitivity of the camera based on available light and effects photographer is after.

In simple terms ISO ranges from 100 (starts at 200 in some cameras) and goes as follows: 100-200-400-800-1600-3200… where each step doubles the sensitivity of the camera. The tradeoff will be added noise levels beyond certain ISO levels. Different cameras have different High ISO performance. Where 400-800 used to be the highest “usable” ISO for cameras a few years back, we now see near noise free pictures at ISO levels higher than 1600 on many newer cameras.

Full frame and Cropped sensor cameras are very different with Full Frame cameras having improved noise performance at High ISO. This is a topic beyond the purpose of this article, but it might be worth considering that when choosing a new camera body if the photographer finds himself shooting at higher ISO frequently.

Other factors such as correct exposure can also affect noise levels as increasing exposure of an underexposed shot in post-processing can add to the noise. Also, sharpening can increase noise levels.

Effect of ISO on image exposure at same aperture and shutter speed. Notice the added noise which is more visible in darker areas of the image and more on the ISO 3200 image.

6. Depth of field

As mentioned before, Depth of Field (DOF) is the measure of how much of the picture is in focus (not blurred) around the focus point. Artistically, blurring anything beyond your subject (when taking a portrait for example) gives a nicer effect with more emphasis on the subject. Yet from a documentation perspective, if one wants to show a larger coral in the highest quality shot, then maybe having more DOF will serve the purpose best.

In discussing DOF, many will jump to aperture discussion. While true aperture does determine DOF, there are other factors to consider as well.

a. Aperture:

As mentioned above

Larger aperture --> Smaller Aperture Number --> Shallow DOF (less areas in focus)

Smaller Aperture --> Larger Aperture Number --> increased DOF (more areas in focus)

This also links to how much one can close or open the aperture based on available light.

Increasing DOF with smaller aperture… Notice the decrease in exposure as aperture decreases (larger number). 1st and last shot are at the same aperture with shutter speed adjusted for good exposure, notice the added DOF on corals in the background.

b. Focal length used.

This gets a bit complicated but the easy explanation is the more you zoom (longer focal length used), the less DOF you get.

This is a bit limited in aquarium photography due to limited aquarium widths usually.

Pictures shot at same aperture and different focal lengths. DOF decreases with zoom visible on background corals.

c. Distance to subject

Moving the camera away from the subject will increase DOF. This is useful for full tank shots (FTS) where aquarium lighting usually requires a larger aperture to allow as much light in as possible and therefore results in areas in front and behind the focus point looking blurred. Moving back does add to the depth of field, so shooting with very wide apertures can still show the front and back of the tank well.

Pictures at 3.2 and 3.5 of a 34-inch-wide tank shot at distance from front glass, showing good DOF

7. Focusing

Focusing techniques and in-camera technology for better focusing are beyond the scope of this article, but we’ll go through a few tips on how to better focus for optimizing pictures.

Looking at the factors mentioned above, limited light, moving fish, swaying corals, and also having to be perpendicular to glass might limit the ability of better positioning of the camera to facilitate focusing by putting the Autofocus point on an area with more contrast.

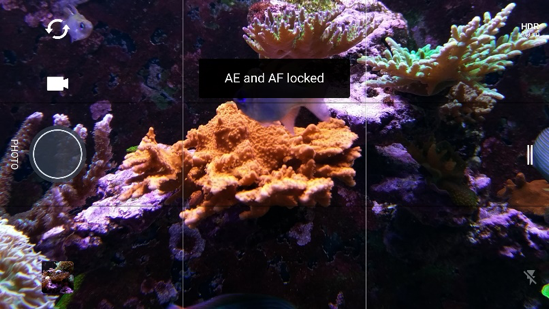

Locking focus and repositioning is very important. This involves half pressing the shutter so that the camera focuses and locks the focus (also valid for mobile phone cameras by long pressing on area to focus—most mobiles will lock focus and exposure on that area), then moving the camera to a better position keeps the same area in focus. It’s important not to move the camera extensively back or forth to avoid having the subject out of focus. So, slight movements to the right are left, up or down are acceptable.

Manual focus use is very limited in aquarium photography, and the only times I resort to it is when using extension tubes or reverse lenses… which limit focus. This can of course be made easier by utilizing macro focusing rails which control moving camera back and forth to focus. Again, this is beyond the scope of this article.

Macro rail and extension tubes for high magnification macro

8. Noise

With swaying corals and moving fish, shooting with fast shutter speed is a must to avoid motion blur which results in needing to use higher ISO to make better use of the minimum light. High ISO adds to noise levels. Compensating with wider apertures is limited on some non-pro lenses (their range is limited), and there is difficulty in photographing corals using wider apertures due to the limited DOF. One added result of having to use fast shutter speeds, higher ISO, and having limited light in most tanks is that shots are more likely to come out a bit underexposed. Increasing exposure in post processing is an easy fix, but this also results in creating a bit more noise in the picture. Sharpening in post processing for printing purposes or to increase crispness in an image will also make noise more noticeable in the pictures.

Pictures at Iso 3200-1600-800- 400. Notice the apparent noise at 3200 and 1600 which decreases at 800 and 400. Aperture and shutter speed were modified to keep the exposure level acceptable, aperture and shutter speed modified to keep exposure levels, minimal exposure and sharpening adjustment in Photoshop which adds to the noise level.

9. Lighting

One of the most discussed topics in aquarium photography is white balance. White balance directly relates to lighting used. Different types of lights are used to light up tanks—from T5s, MH, and lately LEDs. To make it more difficult, all of these lights have inconsistencies like different bulbs in front than in mid or back of the tanks for T5s, different Kelvin (or light color) for halides, and the one with most variations is definitely LED (particularly as vendors allow reefers to tweak each color in the spectrum to their liking). A combination of Halides and T5s previously and, more recently, hybrid lighting incorporating LED and T5 and also MH and LED have made lighting differences even more of an issue with a different color shades found from one spot to another in the same tank. T5 lighting does provide a more consistent shadowless light, MHs are a bit easier to shoot with less color variations (Same Kelvin rating) to worry about.

Different K rating on Halides makes it more or less challenging. While 10K might be the easiest to shoot under and correct for colors, 14K is somehow a more pleasing light with more color pop. White balance correction can still be pretty straightforward with these ranges. 20K MH lighting becomes challenging with more blue hues to correct for.

LEDs are the most challenging with different and even changing intensity, colors and shadows that might change throughout a photo shoot due to the lights’ daily cycle. Having more blue in the lighting makes it very difficult for cameras to correct for white balance in camera, and so post-processing is absolutely necessary (and even that is not guaranteed to work). Increasing whites and decreasing blues might be necessary for good results.

10. White balance

White balance—the most discussed topic in tank photography. I’ve been on aquarium photography boards for more than 15 years, and more questions are asked about this than any other issue.

Looking at the color of lights (discussed above) and understanding camera limitations to handle different Kelvin temperatures, post-processing is essential for dealing with white balance issues.

A couple of things that can help reduce the blue tint in pictures:

Decreasing blue in lights and increasing whites during a photo shoot.

Experimenting with built in white balance presets (cloudy works the best usually) or experimenting with custom white balance settings (where a picture of a gray object is photographed under tank lighting and the camera corrects it to bring it back to gray and memorizes the correction) is often necessary. Different cameras have different ways to go through this. You can find your camera’s instructions for white balance adjustment in the camera’s user manual.

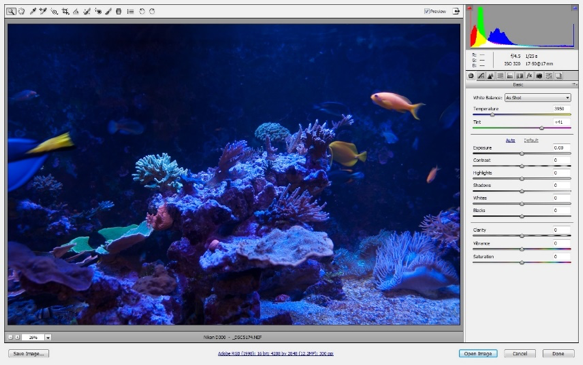

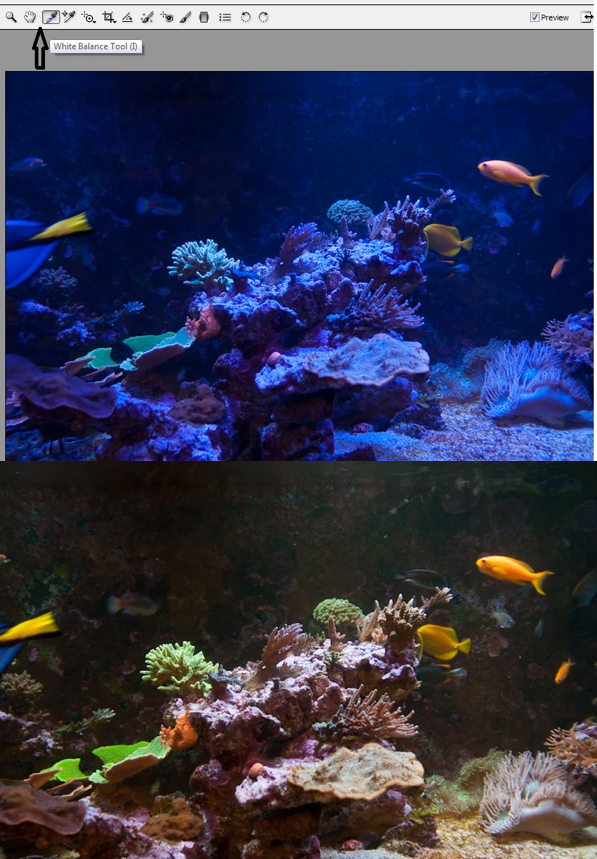

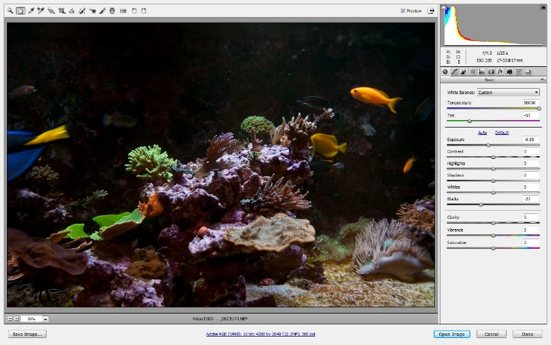

Correcting for White balance in post-processing is easier if one shoots in RAW format. Photoshop offers the ability to correct WB with a K slider that we can move close to the K reading of the lighting used. Another very easy method is to use the white balance tool where the only thing to do is to pick a gray colored structure in the picture (any rock will do) and Photoshop will automatically correct the WB. Clicking on few shades of gray in the pic will give slightly different results, and one only has to choose the correction closest to real colors. Working with JPEGS is a bit less forgiving and the correction tools are a bit more limiting.

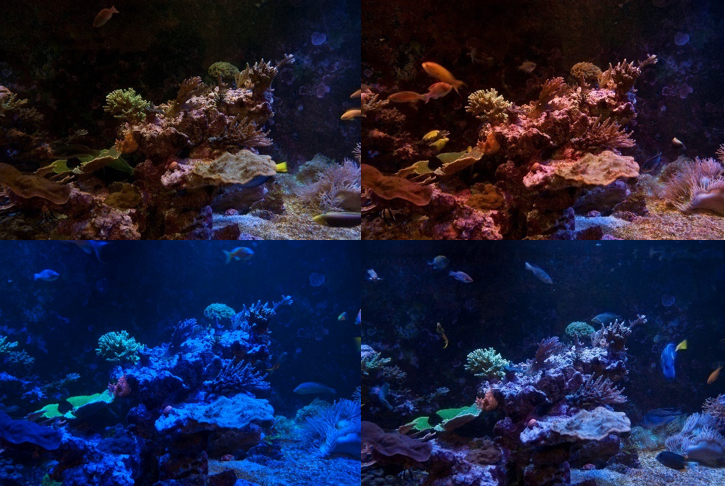

Color tints from different color channels on LED

Correcting for white balance when shooting with Raw is pretty straightforward.

Open Raw image in Adobe Raw editor

Either use the temperature or tint sliders on the top right or chose the white balance tool. I find the white balance tool to be pretty good, and I fine tune it using the temperature and tint sliders.

Fine tune with temperature and tint sliders

This concludes our treatment of photography basics. Feel free to comment below with your own insights or questions. Also, be sure to check out our next installment in our photography series which will address how to prepare for a photo shoot. Here's the link:

Your Guide to Aquarium Photography #2 - Preparing for a Photoshoot

Fast forward 10 years, and we find ourselves utilizing digital point and shoot cameras (which have come a long way I must admit), entry level DSLRs, crop sensor DSLRs, and again back to full frame DSLRs, and (to make it weird) even small mobile phone cameras that surprisingly can now compete with high-end DSLRs (or so our minds have evolved to think)!

Understanding photography principles relates to understanding the physics behind it. This learning curve can really annoy many people (myself included). I did my best to read up on those principles and to understand them to some extent, but I found out that testing those and seeing the results in actual shots is the best way to fully understand. This 6-part article series won’t delve into complex photography physics and will focus more on straightforward facts and representative pictures to show the effects. In this article, I will address the following list of topics which are most frequently mentioned on aquarium photography forums:

1. Challenges of aquarium photography

2. Camera positioning and stabilization

3. Aperture

4. Shutter speed

5. ISO

6. Depth of field

7. Focusing

8. noise

9. Lighting

10. White balance

In future articles in this series, I will devote time to covering:

11. Preparing for a photoshoot

12. Fish/Coral Camera settings

13. Shooting with Cameras Vs Mobile phones

14. Taking better pictures with mobile phone cameras

15. Top down shots

16. Post-processing

1. Challenges of Aquarium photography

The following factors make photographing fish and corals in tanks at least different or more challenging than common photography:

To start with, we are shooting through a thickness of glass. Remember that photography lenses are mostly expensive due to the high cost of high end glass used (a lens or a zoom is a series of internal lenses used and, of course, technology like vibration reduction, autofocusing mechanism…). Another type of glass that we shoot through is the expensive lens filters that are added in front of lenses for some effects. These are simply a piece of glass with a mount. Now consider shooting through an increased thickness of green tinted glass with algae film buildup and scratches. Furthermore, we are often shooting at even more thickness than we think simply because we may angle the camera a bit instead of being totally perpendicular to the aquarium glass which can only increase distortions. To make it even worse, the aquarium glass adds the challenge of reflection that can limit use of flash.

An additional challenge is the particles floating in the water, distorting the clarity of the photo. The medium we’re shooting in (water) also plays an important role. Keep in mind, this is water where we have flow…stirring all sorts of debris from feeding and fish excrements, as well as particles released from some corals. Tank water is not always clear and can have a yellowish/green tint (Don’t believe me? Simply compare two cups tank water/fresh water). We’ll go through some techniques to make sure the water is as clear as possible before a photoshoot which can help, yet we have to keep in mind that water is not as clear as we perceive it to be, and this will lead to some challenges. To make it worse certain fish are constantly picking algae from rocks, picking the sand for critters or even diving in the sand which makes for frequent release of particles we have to deal with when taking pictures.

Additional challenges are the subjects we shoot which are constantly on the move. This makes photographing a fish even more difficult than getting a 5-year-old to stay still for a picture. Even corals are mostly swaying in the current, and stopping the flow can lead to unnatural shapes or at least take away from their beauty.

Tank lighting is one of the most difficult challenges to deal with, and LEDs have made it so much more difficult to take good-looking pictures with natural looking colors. Unfortunately, cameras can’t “see” or correct for white balance the same way our eyes and mind can, which results in blue-looking pictures most of the time. Oddly, our minds have somehow accustomed to that and I see blue pictures shared on forums and on social media. It’s even worse for out of focus pictures (which I will go through when discussing aperture and DOF).

2. Camera positioning and stabilization

Considering that we are shooting through glass as described above, it makes sense to minimize distortion by shooting through the least amount of glass. The easiest way to do this is to be totally perpendicular to the glass. Refraction and reflection are also the least when we take photos at a perpendicular angle rather than at an oblique angle.

Oblique camera position and resulting distortions in the picture

Glass can also make it more challenging with reflections from ambient lighting as well as from flash lighting used.

Ambient light reflections showing 2 different effects based on tank lighting

To best cope with ambient light and reflections, dimming room lights, closing shutters and positioning front lens (it’s better to have a lens hood on to avoid scratches and to better tell if the camera is perpendicular to front glass)

If shooting handheld rather than with a tripod, using a lens hood can also offer a level of support to avoid handshake. If on a tripod, I also try to position the camera so that the front lens is perpendicular and very close to the glass in order to avoid reflections and distortions. This level of close proximity to the aquarium also serves to keep tiny scratches that might be in the tank glass invisible in pictures. Cameras also have a minimum focus distance which causes obstructions in close proximity to the lens to become blurred, and consequently, they won’t appear in the picture. This is useful for avoiding scratches and tiny algae spots on glass from showing in your photo.

Camera hand held Perpendicular to glass

(Top down shots are gaining in popularity lately, especially as most corals posted for sale online are shot top down, we’ll discuss those in a later article in this series).

A steady tripod is a must in tank photography as we are mostly shooting at reduced shutter speed due to lower light levels, this increases the chance for camera shake. I find a good tripod and a decent tripod head (tripods and tripod heads come separate for professional tripods which allow you to match tripod heads to the camera and lenses you are using) are very beneficial. Go for sturdier models if shooting with heavy camera/lens combination.

Joystick tripod heads also offer a higher degree of flexibility especially when tracking moving fish, I find them very useful especially when using a monopod VS a tripod. Monopods can be a be a bit easier to carry around and more flexible to use for aquarium photography but not as steady as tripods.

Monopod and joystick head

Tripod and ball head

3. Aperture

Aperture, shutter speed, and ISO are the three photography pillars, and understanding those is crucial to understanding what went wrong (or right) in a picture and how to correct it or what to do to get a desired effect.

Let’s discuss aperture first. In simple words, aperture is the measure of the size of the opening of the lens when taking a picture. The more open it is, the more light it allows through the lens, which allows the camera to better adjust for dim lighting. However, increased aperture comes at a price which is depth of field (DOF), or how much distance away from our focus point is in focus (not blurred). To make it more complex, the numbers are inverted so the smallest aperture has the biggest number. Different lenses have different apertures—2.8 and below is considered pro.

So basically:

A shot at 2.8 aperture (very wide aperture) will allow more light in, but DOF will be limited.

A shot at 32 (very narrow aperture) will allow very limited light to go through yet it provides more depth of field so that objects before or after the point of focus will appear in focus.

Common aperture numbers go as follows: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22… Reducing aperture size at multiples of one over the square root of two allows half the light into the camera. For example, f/8 will let in 4 times more light than f/16. The effect on depth of field and lighting is clearly seen on the photos of the ruler (see below) where the focus point is on 5.

Pictures at 2.8-4.0 and 8.0 aperture. Focused at 5. Notice how DOF increases with Aperture (more of the image in focus) and how the amount of light in the picture decreases with smaller apertures.

Pictures at 2.8-4.0 and 8.0 aperture. Notice how DOF increases with Aperture (more polyps appear in focus) and how shutter speed was compensated (slower shutter speed for smaller aperture) to keep exposure constant. Last picture shows the effect of increasing aperture without shutter speed compensation which results in a darker image.

4. Shutter Speed

Shutter speed is the length of time set for the shutter to remain open while taking a picture. The more it stays open, the more light goes into the camera, and naturally, the more chance for our subject or hands to move and cause blur to happen. Sometimes blur is a desired effect, and we choose to go with longer exposures to get the blur that reflects motion like moving water in a river. However, in aquarium photography we mostly prefer crisp shots, so faster shutter speeds are used to freeze any motion.

Shutter speed is measured in fractions of a second: 1/1000, 1/500, 1/250, 1/12, 1/60, 1/30, 1/15, 1/8, 1/4, 1/2, 1

Speeds as fast as 1/8000 of a second and as long as 30 Seconds (or even B exposure which leaves the shutter open till manually closed) are available on most newer cameras. Longer exposures are rarely needed in aquarium photography, and ultra-fast exposures are rarely possible with limited tank lighting.

Flash is frequently used to freeze the motion of a fish while a little longer exposure can gather up enough light to illuminate the background or a fast shutter speed is used to black out the background

Motion blur visible at shutter speed of 1/6 and decreases at shutter speeds of 1/25 and 1/60. Shutter speeds of 1/125 possible by increasing ISO to 400 and to avoid a very wide aperture that would minimize DOF.

Effect of shutter speed on motion blur, with fish looking blurry on shutter speed of 1/20 with particles in the water looking blurred as well.

Shutter speed of 1/125 to freeze motion, flash used to keep a good exposure.

5. ISO

ISO is the camera’s sensitivity to light. In film days, different films had different sensitivity and selection was based on what type of subjects were being photographed.

Digital photography has made it easy to switch ISO (a simple button click now), which modifies the sensitivity of the camera based on available light and effects photographer is after.

In simple terms ISO ranges from 100 (starts at 200 in some cameras) and goes as follows: 100-200-400-800-1600-3200… where each step doubles the sensitivity of the camera. The tradeoff will be added noise levels beyond certain ISO levels. Different cameras have different High ISO performance. Where 400-800 used to be the highest “usable” ISO for cameras a few years back, we now see near noise free pictures at ISO levels higher than 1600 on many newer cameras.

Full frame and Cropped sensor cameras are very different with Full Frame cameras having improved noise performance at High ISO. This is a topic beyond the purpose of this article, but it might be worth considering that when choosing a new camera body if the photographer finds himself shooting at higher ISO frequently.

Other factors such as correct exposure can also affect noise levels as increasing exposure of an underexposed shot in post-processing can add to the noise. Also, sharpening can increase noise levels.

Effect of ISO on image exposure at same aperture and shutter speed. Notice the added noise which is more visible in darker areas of the image and more on the ISO 3200 image.

6. Depth of field

As mentioned before, Depth of Field (DOF) is the measure of how much of the picture is in focus (not blurred) around the focus point. Artistically, blurring anything beyond your subject (when taking a portrait for example) gives a nicer effect with more emphasis on the subject. Yet from a documentation perspective, if one wants to show a larger coral in the highest quality shot, then maybe having more DOF will serve the purpose best.

In discussing DOF, many will jump to aperture discussion. While true aperture does determine DOF, there are other factors to consider as well.

a. Aperture:

As mentioned above

Larger aperture --> Smaller Aperture Number --> Shallow DOF (less areas in focus)

Smaller Aperture --> Larger Aperture Number --> increased DOF (more areas in focus)

This also links to how much one can close or open the aperture based on available light.

Increasing DOF with smaller aperture… Notice the decrease in exposure as aperture decreases (larger number). 1st and last shot are at the same aperture with shutter speed adjusted for good exposure, notice the added DOF on corals in the background.

b. Focal length used.

This gets a bit complicated but the easy explanation is the more you zoom (longer focal length used), the less DOF you get.

This is a bit limited in aquarium photography due to limited aquarium widths usually.

Pictures shot at same aperture and different focal lengths. DOF decreases with zoom visible on background corals.

c. Distance to subject

Moving the camera away from the subject will increase DOF. This is useful for full tank shots (FTS) where aquarium lighting usually requires a larger aperture to allow as much light in as possible and therefore results in areas in front and behind the focus point looking blurred. Moving back does add to the depth of field, so shooting with very wide apertures can still show the front and back of the tank well.

Pictures at 3.2 and 3.5 of a 34-inch-wide tank shot at distance from front glass, showing good DOF

7. Focusing

Focusing techniques and in-camera technology for better focusing are beyond the scope of this article, but we’ll go through a few tips on how to better focus for optimizing pictures.

Looking at the factors mentioned above, limited light, moving fish, swaying corals, and also having to be perpendicular to glass might limit the ability of better positioning of the camera to facilitate focusing by putting the Autofocus point on an area with more contrast.

Locking focus and repositioning is very important. This involves half pressing the shutter so that the camera focuses and locks the focus (also valid for mobile phone cameras by long pressing on area to focus—most mobiles will lock focus and exposure on that area), then moving the camera to a better position keeps the same area in focus. It’s important not to move the camera extensively back or forth to avoid having the subject out of focus. So, slight movements to the right are left, up or down are acceptable.

Manual focus use is very limited in aquarium photography, and the only times I resort to it is when using extension tubes or reverse lenses… which limit focus. This can of course be made easier by utilizing macro focusing rails which control moving camera back and forth to focus. Again, this is beyond the scope of this article.

Macro rail and extension tubes for high magnification macro

8. Noise

With swaying corals and moving fish, shooting with fast shutter speed is a must to avoid motion blur which results in needing to use higher ISO to make better use of the minimum light. High ISO adds to noise levels. Compensating with wider apertures is limited on some non-pro lenses (their range is limited), and there is difficulty in photographing corals using wider apertures due to the limited DOF. One added result of having to use fast shutter speeds, higher ISO, and having limited light in most tanks is that shots are more likely to come out a bit underexposed. Increasing exposure in post processing is an easy fix, but this also results in creating a bit more noise in the picture. Sharpening in post processing for printing purposes or to increase crispness in an image will also make noise more noticeable in the pictures.

Pictures at Iso 3200-1600-800- 400. Notice the apparent noise at 3200 and 1600 which decreases at 800 and 400. Aperture and shutter speed were modified to keep the exposure level acceptable, aperture and shutter speed modified to keep exposure levels, minimal exposure and sharpening adjustment in Photoshop which adds to the noise level.

9. Lighting

One of the most discussed topics in aquarium photography is white balance. White balance directly relates to lighting used. Different types of lights are used to light up tanks—from T5s, MH, and lately LEDs. To make it more difficult, all of these lights have inconsistencies like different bulbs in front than in mid or back of the tanks for T5s, different Kelvin (or light color) for halides, and the one with most variations is definitely LED (particularly as vendors allow reefers to tweak each color in the spectrum to their liking). A combination of Halides and T5s previously and, more recently, hybrid lighting incorporating LED and T5 and also MH and LED have made lighting differences even more of an issue with a different color shades found from one spot to another in the same tank. T5 lighting does provide a more consistent shadowless light, MHs are a bit easier to shoot with less color variations (Same Kelvin rating) to worry about.

Different K rating on Halides makes it more or less challenging. While 10K might be the easiest to shoot under and correct for colors, 14K is somehow a more pleasing light with more color pop. White balance correction can still be pretty straightforward with these ranges. 20K MH lighting becomes challenging with more blue hues to correct for.

LEDs are the most challenging with different and even changing intensity, colors and shadows that might change throughout a photo shoot due to the lights’ daily cycle. Having more blue in the lighting makes it very difficult for cameras to correct for white balance in camera, and so post-processing is absolutely necessary (and even that is not guaranteed to work). Increasing whites and decreasing blues might be necessary for good results.

10. White balance

White balance—the most discussed topic in tank photography. I’ve been on aquarium photography boards for more than 15 years, and more questions are asked about this than any other issue.

Looking at the color of lights (discussed above) and understanding camera limitations to handle different Kelvin temperatures, post-processing is essential for dealing with white balance issues.

A couple of things that can help reduce the blue tint in pictures:

Decreasing blue in lights and increasing whites during a photo shoot.

Experimenting with built in white balance presets (cloudy works the best usually) or experimenting with custom white balance settings (where a picture of a gray object is photographed under tank lighting and the camera corrects it to bring it back to gray and memorizes the correction) is often necessary. Different cameras have different ways to go through this. You can find your camera’s instructions for white balance adjustment in the camera’s user manual.

Correcting for White balance in post-processing is easier if one shoots in RAW format. Photoshop offers the ability to correct WB with a K slider that we can move close to the K reading of the lighting used. Another very easy method is to use the white balance tool where the only thing to do is to pick a gray colored structure in the picture (any rock will do) and Photoshop will automatically correct the WB. Clicking on few shades of gray in the pic will give slightly different results, and one only has to choose the correction closest to real colors. Working with JPEGS is a bit less forgiving and the correction tools are a bit more limiting.

Color tints from different color channels on LED

Correcting for white balance when shooting with Raw is pretty straightforward.

Open Raw image in Adobe Raw editor

Either use the temperature or tint sliders on the top right or chose the white balance tool. I find the white balance tool to be pretty good, and I fine tune it using the temperature and tint sliders.

Fine tune with temperature and tint sliders

Your Guide to Aquarium Photography #2 - Preparing for a Photoshoot

Last edited by a moderator: